Researchers explore artificial intelligence, cybersecurity and more at the Institute for Human & Machine Cognition.

By Chris Gerbasi | Photos courtesy IHMC

For most people over a certain age, the phrase “artificial intelligence” always had an otherworldly, futuristic connotation to it, along with a sinister implication that computers and robots would one day take over the world.

With the volume of smartphones, automation and seemingly unlimited surveillance, many people today likely feel that this vision has already come true. Artificial intelligence (AI) is utilized to help devices and systems perform tasks, such as visual perception, speech recognition and problem-solving, that normally would require human intelligence.

“Technology developed in AI research is found in every router, in all modern automobiles, smartphones, search engines and elsewhere,” said Ken Ford, co-founder and CEO of the Florida Institute for Human & Machine Cognition, which has headquarters in Pensacola and a branch research facility in downtown Ocala.

“In the near future, automobiles, buses and trucks will operate with increasing automation, often in a mode akin to an autopilot in an aircraft,” he added. “Medical diagnostic systems will increasingly rely on AI as well as much else. Most applications of AI are not standalone intelligence systems, but rather AI is increasingly embedded in nearly everything.”

These days, Ford is focused on an app more serious than a selfie. He serves on the 15-member National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, an independent federal panel that makes recommendations to integrate AI into national security programs. The commission is broadly looking at how global AI developments might affect national security aspects, including competitiveness, the military and ethical considerations of the applications of AI, he said.

“Just as AI is all around us in everyday life, we anticipate the same widespread application of AI in military affairs,” he said. “The countries that ‘win’ the AI competition will be strongly advantaged in both war and peace.”

The commission expects to release a final report in spring 2021. In October, commissioners released a 268-page interim report to the president and Congress that urged the immediate implementation of 66 recommendations in three areas, briefly summarized here:

Competition: Create a Technology Competitiveness Council to develop and implement a national technology leadership strategy and integrate relevant technological, economic and security policies; enhance collaboration with industry partners on AI research and development and enable faster transition of successful technologies; and develop holistic strategies across a variety of sectors to sustain U.S. competitiveness.

Innovation and talent: Provide AI researchers with resources and space to pursue innovative ideas that will push the frontiers of technology; expand the national pool of AI and STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) talent to improve both the economy and national security by creating new career paths for military and civilian government employees; improve STEM and AI education; and develop an AI-proficient workforce.

International cooperation: Expedite the responsible development of AI by NATO and member states and shape defense cooperation agreements with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific; build a multilateral effort to advance the use of AI and ensure new emerging technology standards are based on technical considerations and best practices, not political manipulation, and address national security needs; and form a tech alliance between the U.S. and India, and a strategic dialogue between the U.S. and the European Union, to address the challenges and opportunities presented by AI.

In short, the commission states that the United States must build on the strength of its allies and partners to win the global technology competition and preserve free and open societies.

It’s no surprise that Ford was named to the commission. He’s considered one of the world’s leading AI researchers, and his impressive résumé includes several other national board appointments along with the directorship of NASA’s Center of Excellence in Information Technology.

Ford, Alberto Cañas and Bruce Dunn co-founded IHMC in 1990 when they were colleagues at the University of West Florida, and the 501(3)(c) not-for-profit organization is part of the State University System. The Ocala facility, in the former public library building, opened in 2010.

The bulk of IHMC research is done for the U.S. government, which funds projects through contracts. The institute works with NASA, the departments of Defense and Energy, the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), the Intelligence Advanced Research Project Agency (IARPA), private foundations as well as commercial partners. IHMC also receives funding from grants, donors and the state, said Laurie Zink, development and community outreach director.

Research of artificial intelligence, along with robotics, cybersecurity, language processing, health and many more fields, supports IHMC’s mission to optimize the physical and mental capabilities of humans. The work has resulted in stunning achievements with humanoid robots, exoskeletons to improve mobility for paraplegics and exercise machines for NASA astronauts in space, to name a few.

“For those of us working at IHMC, AI is less about ‘artificial’ intelligence and more about ‘amplified’ or ‘augmented’ intelligence,” Ford said. “We are interested in cognitive orthotics, that is, technological systems that leverage and extend human cognition.”

CYBER BATTLES

IHMC research in the areas of security and information assurance also includes the protection of the nation’s critical infrastructure and cyberinfrastructures. Teams are not contracted to protect specific data but rather to create frameworks and research paradigms and theories about how data should be protected, research scientist Adam Dalton said. Dalton and colleagues Bonnie Dorr and Larry Bunch form a team working on several cybersecurity projects at the Ocala branch.

Dalton, who also specializes in natural language processing, said his current research is focused on how to use human language technology to improve cybersecurity and information security, especially in large online communities. This type of work strives to thwart cyberattacks that may try to create remote network connections, delete all files in a system or access sensitive data like government personnel records, medical office health records or company salaries. Or, the defense technology might track the source of bogus emails asking an office worker to buy gift cards for the boss.

For example, in the Moving Target Command and Control project, Dalton and other researchers designed moving target defenses designed to fight off an adversary. He explained that an adversary spends a lot of time and effort to compromise a secure network: discovering the vulnerabilities in the network, developing the exploitive tactics that could compromise those vulnerabilities, weaponizing them and gaining a “posture” inside the network that allows the adversary to send commands back and forth.

The moving target defenses were designed to make sure that the network posture was constantly changing, so that all the time, energy and resources the adversary invested into compromising one configuration of the network would then be wiped out when that posture changed. The approach was designed to prevent the attack and then, by making that change, the adversary would need to respond, making them “noisier” and easier to detect. The work allowed mission-critical elements of the system to be retained while getting the adversary out of the system, Dalton said.

Another project, Active Social Engineering Defenses, involved actively engaging an adversary in a “game” of cat and mouse. Researchers developed a chat bot that monitored the inboxes of personnel within an organization and detected any “social engineering” attacks or queries of personnel to perform tasks with social or language cues.

In their attempts to run scams, cybercriminals look at company or university websites to find out who’s in charge – CEOs, deans, chairmen – and who reports to them, Dalton said.

“From there, it’s super-easy,” he said. “You just put that person’s name in (an email), and say, ‘Hey, can you do something real quick for me? I need you to buy gift cards,’ for whatever reason, ‘and send me those gift cards.’ And it’s a simple attack, a simple premise and it is easy to tailor from one organization to the next, and because of that, the criminal can scale it up to a huge amount. Then, even if they get an extremely low success rate, they can still make a lot of money from it. But the counter of that is it’s also very easy for computers to detect.”

The defense requires understanding the social network of an individual’s computer: who do they usually talk to, what do they usually talk about, what kind of tasks are they asked to do? Then it’s easier to see when they receive an attack email.

The vulnerability in this case was at the social level, not the technical level, Dalton said, and that’s where language processing research came in handy. The researchers developed new natural language technology that focused on the “ask” and the “framing” of the emails: what are they asking you to do, and why would you do what they’re asking?

The chat bot also could extract information that might lead to identifying the source of the attacks and whether national defense officials or law enforcement needed to be alerted.

“By studying the attacker’s tools and techniques, we can then turn those against them, which made it a lot of fun,” Dalton said.

Social engineering defenses are useful for companies like Microsoft, Google and others that manage large email platforms, he said. Those companies would be interested in knowing how attacks are being carried out and whether their own technology is being used to conduct the attacks.

In cybersecurity, it’s helpful to understand the human elements as well as the technical elements, Dalton said.

“You need to have that social science, that linguistic and the technical acumen to do this research,” he said. “So, having the people who have both the knowledge to perform the individual area of (expertise) and also the willingness to branch out beyond what they’re expert in and work with other people who have different expertise, I think that’s one of the things that has been so great and allowed us to be successful.”

Seeing the practical applications of his research is what drew Dalton to cybersecurity.

“Cybersecurity’s a funny discipline because in an ideal world, you wouldn’t need it. The best way to succeed in cybersecurity is for nobody to know that you’re doing anything,” he said. “By being successful in cybersecurity, you allow other people to be successful in other ways, and I think that’s the rewarding part.”

THE IHMC CULTURE

Humans interact with machines all day long, but that connection means a little more to the researchers at the institute.

“IHMC really does focus on that space where humans and computers and robots intersect,” Dalton said.

The staff consists of professors, scientists, doctors, astronauts, engineers, philosophers and guest researchers from around the world. Up to 150 people work at the Pensacola site, while about 15 staff members work in Ocala, a location chosen for its proximity to universities and sites such as the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne.

IHMC’s approach to attracting talent is not typical for a research organization, Ford said.

“Our primary recruiting method is that we talk amongst ourselves and identify someone who we think would be a wonderful colleague and then we pursue that person,” he said. “We look for passionate, intellectual risk-takers who have an entrepreneurial bent and need little management or supervision.”

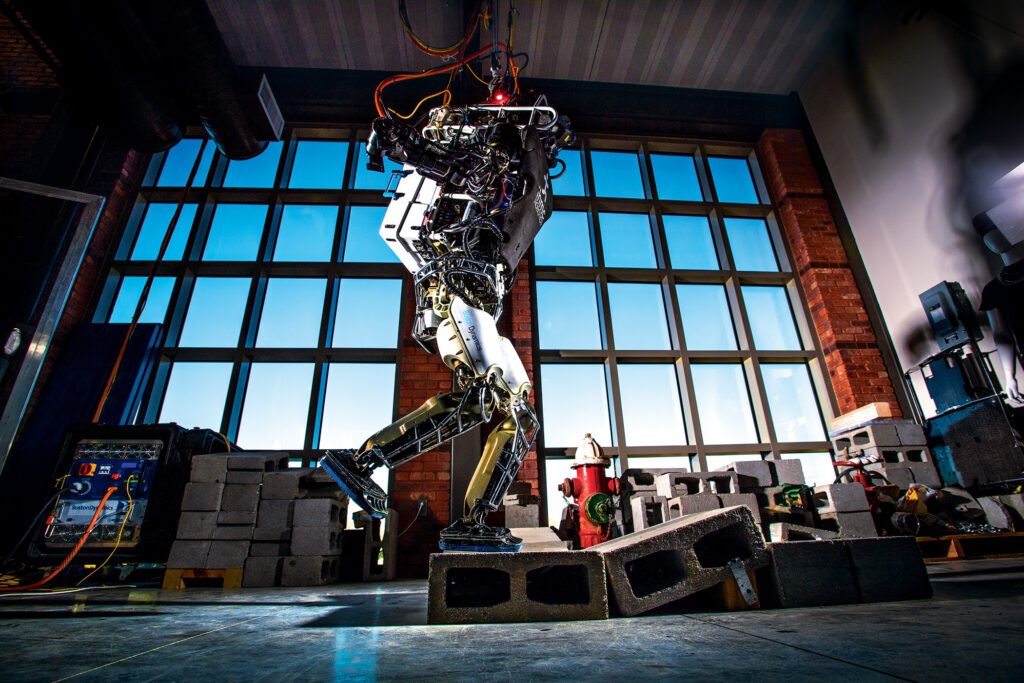

Those risk-takers have paid off with big rewards. Robotics work led by senior research scientist Jerry Pratt became the focus of a Time magazine story in June 2015. IHMC was provided with a robot chassis made by Boston Dynamics and Carnegie Robotics. The IHMC team developed a control system for the robot, nicknamed Atlas, which was designed to aid rescue operations in disaster zones. Atlas won a competition for humanoid robots sponsored by DARPA, a government agency that funds tech projects. In the contest, the robots were programmed to drive a vehicle, climb a ladder, turn off valves and perform other tasks.

IHMC also developed a powered exoskeleton device that provides paraplegics with increased mobility and independence. In 2019, a team led by senior research scientist Peter Neuhaus received a $500,000 grant as part of a $4 million program sponsored by the Toyota Mobility Foundation, allowing the team to further develop the prototype, according to an IHMC newsletter.

Another team formed by Neuhaus worked with NASA on an exercise machine for astronauts during long-term flights and stays at the International Space Station.

“In developing this piece of equipment for them, it became very obvious that this would work very well with older populations,” said Zink, explaining that the machine is now moving from the research stage to development and marketing for use in everyday life.

Zink said there are about 100 projects going on at IHMC at any given time. The larger Pensacola site houses the robotics lab, as well as a giant blue sphere that rotates people inside to evaluate how movement affects vision and balance, she said. Cybersecurity and natural language processing (NLP) are the central research fields studied at the Ocala facility.

For example, research scientist Archna Bhatia explores NLP in the medical domain. She has been working on developing noninvasive techniques for detection and monitoring of physiological, psychological and neurological conditions. She developed a noninvasive, speech-based method for detection and monitoring of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) based on divergence from the asymptomatic speech, the IHMC website states.

Bonnie Door is an associate director and senior research scientist at the Ocala facility. Together with colleagues, Dorr established the new field of Cyber-NLP, bringing together expertise at the intersection of cyber, social computing, AI and NLP. She focuses on cyber-event extraction and natural language understanding for detecting attacks, discerning intentions of attackers and thwarting social engineering attacks.

While the institute is part of the university system, it is not a university itself, so researchers feel more autonomy in their work and are able to collaborate more, Zink said. The areas of study often intertwine. The institute promotes a collegial atmosphere and a “cross-pollination” of expertise in which researchers of one project may lend a hand to another project.

“A lot of people here really enjoy the outreach aspects of research and education, and other people really like being able to spend all day, head down, working on advanced technology projects,” Dalton said. “I think that’s one of the things that draws academics to IHMC … if you have a good idea and you’re able to convince somebody it’s a good idea worth funding, then you’ll probably be able to find a home for it here and find some of the most incredibly well-educated people around to work on that with you.”

Ford said he is particularly proud of the culture that team members have built together. Dalton, who joined IHMC in 2012, caught a glimpse of that culture several years earlier when he toured the Pensacola facility. He walked right up to people who were building robots and recognized how the researchers combined elements of man and machine to excel.

“That was obvious to me early on, and it was just one of those things that you see it, you talk to the people, you see how excited they are and you see how knowledgeable they are, and it just became a place that I wanted to work,” he said.