From the polished black exterior of his most recent creation, Don Garlits achievements are far from the humble roots of pieced together junkyard cars. No longer painting numbers on the side of rusted-out steel, he has everything at his disposal. As the first person to break 200 mph on the drag strip, he has solidified for himself a place in drag race history. There is no denying that Garlits’ reputation among drag race fans spans numerous continents and multiple generations. In fact, Garlits achievements are so vast it takes an entire museum to house them.

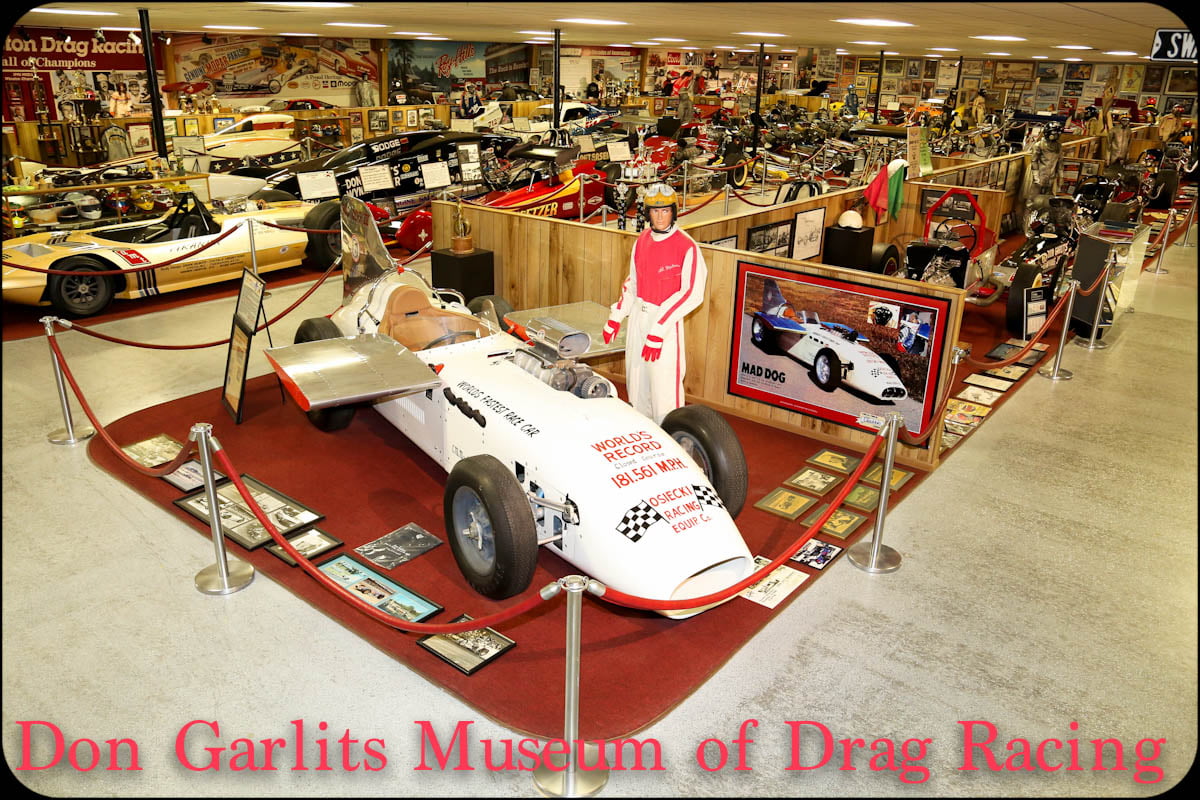

A staple of the Ocala community since 1982, Don Garlits Museum of Drag Racing located just off of I-75 in southwest Ocala sits in an unassuming warehouse. Part museum, part garage—it’s filled with thousands of pieces of memorabilia—each one chronicling his journey. Under the bright florescent lights, rows of dragsters—close to three hundred in total—fill the room. Each vehicle, hand made by Garlits, and raced under his care. Every dragster carries with it a story as colorful as the coat of paint on its exterior. The number of items packed into the expansive building borders on overwhelming, and it’s easy to tell how one can spend hours perusing its contents.

A staple of the Ocala community since 1982, Don Garlits Museum of Drag Racing located just off of I-75 in southwest Ocala sits in an unassuming warehouse. Part museum, part garage—it’s filled with thousands of pieces of memorabilia—each one chronicling his journey. Under the bright florescent lights, rows of dragsters—close to three hundred in total—fill the room. Each vehicle, hand made by Garlits, and raced under his care. Every dragster carries with it a story as colorful as the coat of paint on its exterior. The number of items packed into the expansive building borders on overwhelming, and it’s easy to tell how one can spend hours perusing its contents.

Staring at over 50 years worth of accomplishments, my glazed, deer-in-headlights expression must have been indicative of someone who took a wrong turn and needed direction.

His staff is kind and welcoming as spectators wander through the showroom pointing at each car and gawking in hushed tones. Heading past the pristine aisles of restored race cars, behind the security of this team, is an attached garage. The smell of motor oil and fresh afternoon rain replace the comfort of the air-conditioned showroom as other members of his crew are quietly working on a dragster. This is the part most do not see, the everyday steps that lead to the 50 year journey.

Located on the backlot, within sight of the museum, is a single steel building. Black letters spell out ‘Don’s Garage’ above the door. “No one really comes back here. It’s my private workshop,” he explains. “I only come out here every once in a while. I’ve always got five or six projects.” His latest dragster sits in pieces in the middle of the room as he tweaks it for his upcoming race.

Garlits is welcoming and humble as he shows off his private workstations. It’s a gearhead’s paradise—floor-to-ceiling shelving littered with every tool and car part imaginable. Oversized racing tires hang from the ceiling and boxes of trophies, cast aside not because he feels they lack worth, but because there are so many it’s hard to keep up. “Right now I’m rebuilding a Chrystler Hemi from a water pump from the Everglades.” He smiles. “I got it from the Army Corps of Engineers. Thing pumped billions of gallons of water down there—they were very gracious to give me this motor. “ Ingenuity has been key to Garlits success over the years and one of the main reasons he has been able to maintain his illustrious career.

The juxtaposition of Don Garlits the legend and Don Garlits the man is refreshing. Most who have risen to such a stature carry with them a haughtiness that can tend to be off-putting. But with Garlits, there is no sign of ego, only southern hospitality—a take your time and enjoy the moment approach to life.

His beginnings in drag racing were not as exquisite as his current state. Growing up in Tampa as the son of a dairy farmer, his families aspirations for him were that he would follow suit, but that was never in the cards. He loved cars as much as he loved life, and once he realized that, there was no separating the two. “Coming out of high school, I loved racing. I love fast cars.” He states. “Of course, there was no drag racing then. A friend of mine had a round-track car—and I was a body fender guy—so I helped him paint it and get it all pretty. We went out to the local round track in Tampa, and he was pretty good. He had a nice fast engine…but the wiley old experienced guys just bumped him over the wall and just smashed it all up. It’d still run, but he’d be there with his sledgehammer beating his car trying to make the next heat. I said, “I don’t want to do this kind of racing.” There were only two options when it came to vehicle racing, the round-track or the roads. There were dangers present in both options, so Garlits and his friends—who formed a club where they could race side by side–petitioned the city officials for the use of a local abandoned airstrip located in Zephyrhills. Looking to keep drag racers off of the street, the city immediately granted their request.

“In 1950 there were 18 of us. We had no clocks, no trophies, no classes. We just painted two lines on the asphalt and everybody raced everybody.” He states. “That’s just what I loved. I loved to race—and the fastest car won.” With the west coast already saturated with the James Dean-esque racers, the East Coast was just catching up. “In ’52 it (drag racing) was all black leather jackets and hoodlums.” It was during this time that Garlits would meet his future wife. Yet, with her father disapproving of drag racing, he gave up his custom-made vehicle for a bone-stock Ford sedan.

“In 1950 there were 18 of us. We had no clocks, no trophies, no classes. We just painted two lines on the asphalt and everybody raced everybody.” He states. “That’s just what I loved. I loved to race—and the fastest car won.” With the west coast already saturated with the James Dean-esque racers, the East Coast was just catching up. “In ’52 it (drag racing) was all black leather jackets and hoodlums.” It was during this time that Garlits would meet his future wife. Yet, with her father disapproving of drag racing, he gave up his custom-made vehicle for a bone-stock Ford sedan.

One day, while on a drive together, she spotted a small sign that said “drags today” with an arrow pointing in the direction of the races. Never seeing a drag race before she suggested they go and watch. Not one to say no to a race, he kindly obliged. Stopping at the gate, the ticket taker asked one simple question that changed everything. “Do you want to run it?” With his bone-stock Ford, Garlits again obliged-this time winning first place in his class. The trophy from that race currently sits in his office. One of his most prized possessions, he keeps it close. “There was one guy that was there that was winning everything, and I wanted to be like him. So my wife and I build a ’36 Ford cut down coupe. We went from that to a roadster and from that took the body off and got a dragster. Then I got into Hemi engines, and it just got faster and faster.”

Garlits won his first big race in 1955 in Lake City when the National Hot Rod Association came through town with a regional championship. Winning Top Eliminator in an official NHRA event was a big deal. “I will never forget the president of the club said ‘I guess you’ll retire now’, and I said ‘Why would I do that?’ and he says ‘Because you will never beat the Californians.” It was August of 1955 that this statement was verbalized to Garlits and it was in August of 1957 that he outran the World Champion from California at the World Series of Drag Racing in Cordova, Illinois. This race was especially poignant for Garlits. The driver he defeated was a personal hero of his, so much so that the driver’s poster was tacked up on the walls of his shop. As the first to go over 160 miles an hour, defeating him meant everything. Up to this point, the driver had never been outrun. Lining up on the blacktop, knowing he was going toe to toe with his idol, there was a rush of exhilaration. When the signal for the race was dropped, Garlits did what he was born to do-he crossed the finish line first. “When we came back down the return road for the next round, the President of the association says ‘In all fairness to the world champion we’ll have to see that again.” He laughs. “So they made me run him again, and I outran him again.” It was after this event that Garlits skyrocketed to fame. Dethroning the world champion placed him on the cover of the drag newspapers and every form of media. Wanting to keep his winning streak alive, at each race he took note of what others were doing—researching their wins and losses to see how he could make his cars better. He was methodical in approach, and over the years it has paid off well for him.

Garlits won his first big race in 1955 in Lake City when the National Hot Rod Association came through town with a regional championship. Winning Top Eliminator in an official NHRA event was a big deal. “I will never forget the president of the club said ‘I guess you’ll retire now’, and I said ‘Why would I do that?’ and he says ‘Because you will never beat the Californians.” It was August of 1955 that this statement was verbalized to Garlits and it was in August of 1957 that he outran the World Champion from California at the World Series of Drag Racing in Cordova, Illinois. This race was especially poignant for Garlits. The driver he defeated was a personal hero of his, so much so that the driver’s poster was tacked up on the walls of his shop. As the first to go over 160 miles an hour, defeating him meant everything. Up to this point, the driver had never been outrun. Lining up on the blacktop, knowing he was going toe to toe with his idol, there was a rush of exhilaration. When the signal for the race was dropped, Garlits did what he was born to do-he crossed the finish line first. “When we came back down the return road for the next round, the President of the association says ‘In all fairness to the world champion we’ll have to see that again.” He laughs. “So they made me run him again, and I outran him again.” It was after this event that Garlits skyrocketed to fame. Dethroning the world champion placed him on the cover of the drag newspapers and every form of media. Wanting to keep his winning streak alive, at each race he took note of what others were doing—researching their wins and losses to see how he could make his cars better. He was methodical in approach, and over the years it has paid off well for him.

The ability to handle a vehicle is paramount in drag racing but to become a record-breaking mastermind of the field you need the vision to see the next wave of revolutionary ideas that will take your vehicle from fast to legendary. “The experts said that we would never be able to exceed 169 in the quarter. Where they got that idea from who knows… they’ve reached 340 mph in the quarter-mile now.”

His story, however, is not without its own setbacks. One time in particular almost cost Garlits his hands. Early in his career after a particularly bad accident left his hands burned and unable to open, a doctor gave him little hope for ever racing again. The doctor in charge of his care advised that the only option was to remove Garlits’ hands or the blood pooling in them would become septic and he would not survive. Garlits, who built his life around the refurbishment and racing of vehicles was not accepting that diganosis. After much argument, he sought a second opinion that changed his life. As his next physician began to manually uncurl his fingers, the blood that had pooled in his hands began to flow and, with a little bit of care, he was able to fully recover. That would not be the last time he had an accident that would threaten the life of his career. “In 1987, I had a bad accident in Spokane where I broke three of my vertebrae so I was off and couldn’t race for six months.” During this time his fame carried his career. Offered a position with NBC to do television, he was transferred to their Nashville network where he spent the next 17 years. “I’m watching all these cars, and the sport had just stagnated so I designed this car that I thought would be the next level in drag racing.” He reminisces. The Swamp Rat 32 was a mono-wing dragster. “I put this car together and then hurt my eyes racing it in Gainsville while testing it.” He explains, “They had given me this special chute, and it stopped too fast, and I had detached retinas. So I got a new driver, and he drove it for a while, but I didn’t like not driving the car, so we put it all up.”

In 2001, under the encouragement of a friend, that he took one of his cars out of the museum, put a late-model motor in it and began racing once again. “I got Swamp Rat 34 and I was working on getting it ready to take it to Nationals, and I got a 16-page fax three days before time to leave for NHRA of all the stuff I was going to have to do to this car to run indie and there was no way we could do it, so I pulled the plug on the program.” In the age of social media, the fans spread the word that Garlits would not be running. “I got a call from Gary Capshaw in Las Vegas, Nevada—he had a car that he had been 300 mph in and he said ‘Don, we will just put a nice wrap on mine and you can drive it,’” Garlits states “So I went to Indy and went 303 mph, and it was a thrill. But I was upset about not being able to run my own car. So after the race was over, I had the NHRA tech guy come here and look at my car. And there was just one little tube here that had to be changed. We could have fixed it in 15 minutes—they were just being nasty.”

Not letting the politics get to him, he worked on his car and entered it into the races in 2002. Running a total of 10 races in 2002 (one of which he went 318.54mph) and 10 in 2003 (one of which he went 323.04mph). “At the end of the season in Indianapolis, my last run was 310.81, and my wife always came down to the end of the race when I got out of the car. She said to me ‘Please don’t drive this car anymore. It’s scaring me to death.”’ He states fondly “I said ‘What’s wrong?’ and she says, ‘Look at me,’ and she was just shaking all over like a leaf and I said ‘Oh my god, honey, what’s wrong?” He pauses, “She says ‘You need to go with me to my neurologists—we need to have a talk.’ She had been diagnosed with Parkinson in 2000 and never told me. So I never drove the car again, it’s been put up just like it was and that was the end of my Top Fuel racing.”

Not letting the politics get to him, he worked on his car and entered it into the races in 2002. Running a total of 10 races in 2002 (one of which he went 318.54mph) and 10 in 2003 (one of which he went 323.04mph). “At the end of the season in Indianapolis, my last run was 310.81, and my wife always came down to the end of the race when I got out of the car. She said to me ‘Please don’t drive this car anymore. It’s scaring me to death.”’ He states fondly “I said ‘What’s wrong?’ and she says, ‘Look at me,’ and she was just shaking all over like a leaf and I said ‘Oh my god, honey, what’s wrong?” He pauses, “She says ‘You need to go with me to my neurologists—we need to have a talk.’ She had been diagnosed with Parkinson in 2000 and never told me. So I never drove the car again, it’s been put up just like it was and that was the end of my Top Fuel racing.”

In 2008 Crysler announced the build of a drag pack Challenger prototype. Garlits, who has worked with Crystler since 1961, was extended the invitation to travel to Denver to test one of the prototypes. “They had me match race another driver, and I won the race—it was kind of fun. But when I came back, the wife says ‘How’d ya like the run in Denver?’ I said it was a lot of fun, so she said, ‘Why don’t ya get you one.’” Knowing his wife’s fear of higher speeds, he questioned if she was okay with him racing again. She replied with a laugh, stating, “Honey, 130 mph for you is like walking. Get all of them you want.” Purchasing a couple of these vehicles, he continued to race. It wasn’t long after, that his wife passed away.

“I was in really bad shape. I didn’t want to eat or anything. When my wife died, we were married 61 years, and it was really a lick. I had seen all of my friends that had spouses pass away. Most of us had come out of high school marrying high school sweethearts. It was unbelievable. The husband, or the wife would die and it wouldn’t be a year, and the other one would go, and there wouldn’t be anything wrong with them.” Garlits passion for life was sidelined. With no interest in the business, his daughter continued to carry on the day to day operations. After some time had passed, his daughter convinced him to come to a car show hosted at the museum. “It’s important to keep the mind active as well as the body. Both of them are important.”

After being out of the public eye for quite some time, he reluctantly agreed, and as he mingled with fans discussing his career and the plethora of vehicles that were surrounding them, he ran into Lisa Criger. At the time employed by the Star-Banner, Lisa was there covering the event as a guest of the media. The two clicked instantly, and they’ve been together ever since.

Since that time, Garlits has found the passion for getting behind the wheel and taking another crack at breaking more records. As the first dragster to top 170, 180, 200, 240, 250, 260, and 270 mph and the first to top 200 mph in the quarter-mile, there is no doubt that he has more to add to his list.

Since that time, Garlits has found the passion for getting behind the wheel and taking another crack at breaking more records. As the first dragster to top 170, 180, 200, 240, 250, 260, and 270 mph and the first to top 200 mph in the quarter-mile, there is no doubt that he has more to add to his list.

At 87 years of age, he has not slowed down. Recently racing a battery-operated dragster, he topped out at 189. “We pushed it to 189, and we think it would have run better on the next run, but we had two bad battery cells on the 189. But we broke one of the homemade hubs that drive the wheel. So it just turned one of the wheels loose, and it just spun. Of course, I immediately lifted when I felt the acceleration fall off and it couldn’t be fixed at the track.” Bringing it back to his shop and working on it, they put 4000 amps into the motor. The motor, salvaged out of an old sawmill is a heavy-duty motor that was converted into a high-speed motor. A few short weeks after the dragster was repaired Garlits took it out again, this time breaking the 200 mph record for a battery-operated vehicle.

With win after win under his belt, a museum full of memorabilia, and a fan base that has been with him for more than 50 years, there is no end in sight for Garlits. After each win, there is another goal, another record in his crosshairs. “I’m sure there will be a time when I’m done, but I’m pretty sure that will be just before the funeral—I hope.”