Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. I mean, what ‘s better than a full day of food, football and family? Of course, when you get family together, it’s always fun to share family stories.

Some of my ancestors came over on the Mayflower. Not bad, as Thanksgiving tales go. But the better family story is about Thomas Morton, a relative from my paternal grandmother’s side of the family who arrived in Plymouth in 1624, four years after the Mayflower. He was a lawyer, businessman, author and adventurer who came to the New World seeking his fortune in the trading business.

Cousin Thomas (not sure what relation he is to me, so I’m going with “cousin”) and his partners prospered in their new venture, but they didn’t get along too well with the Puritans, who settled and ran Plymouth. So, in the words of my great-uncle Mike Morton, he “got run out of Plymouth. He was hard to get along with.”

Yes, Cousin Thomas got kicked out of Plymouth by the pilgrims.

Turns out he and his colleagues, who were Anglican not Puritan, liked wine, women and song, and didn’t hold back, much to the Puritans’ chagrin.

Oh, the shame, right?

Not exactly.

Cousin Thomas took his trading business and moved it to what today is Quincy, Massachusetts, and named the new outpost, appropriately, Merrymount (emphasis on “merry”). Some historians describe it as a utopia, given the time and place, where the English welcomed the Native Americans as both friends and trading partners. There also were no restrictions on imbibing liquor, or dancing, or cavorting with Native American women. Things were blissful and bountiful in Merrymount, and that it was prosperous and booming in comparison to Plymouth made its success that much sweeter.

Then came the Maypole of Merrymount.

On May 1, 1627, Cousin Thomas and his cohorts held a May Day party reminiscent of similar celebrations in jolly ol’ England. They brewed a keg of beer, erected an 80-foot Maypole with stag horns adorning the top and invited their Native American friends to join in three days of frivolity.

The Puritans in Plymouth, who controlled the new province of Massachusetts, were not amused. And Cousin Thomas knew it.

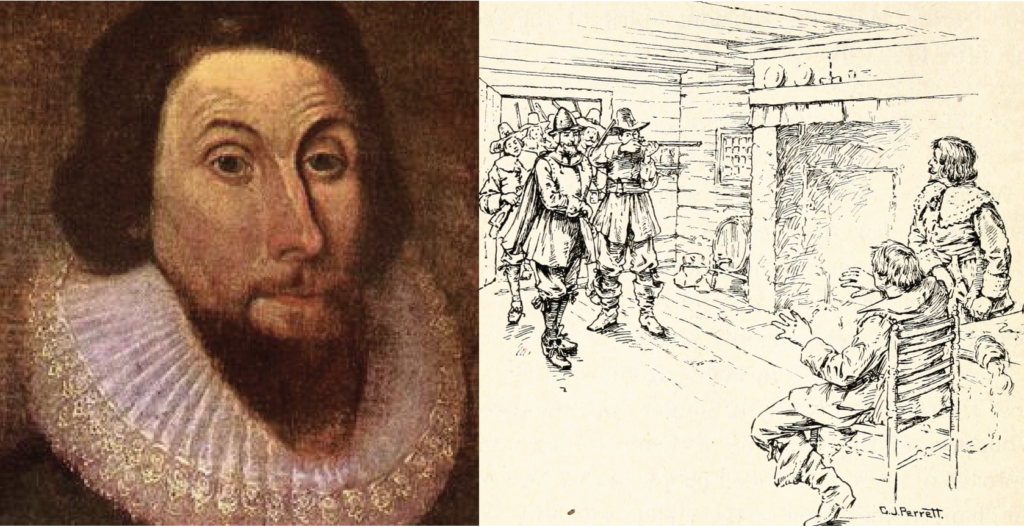

So, when the next May Day celebration came along, and the same kind of celebration took place, the Puritans hired Capt. Miles Standish and armed soldiers to go to Merrymount and end the party – at gunpoint, no less. They arrested Cousin Thomas, cut down the maypole and took him to an uninhabited island six miles off the coast of New Hampshire. There he was dropped off, with only the clothes he was wearing and, as he would later write, “without gun, powder or shot, or dog or so much as a knife to get anything to feed on.”

Luckily, Cousin Thomas had made friends with the Native Americans, who came to his rescue, bringing him food, drink and weapons. Eventually he caught a ride on a passing English fishing ship back to England.

He would return to Merrymount two years later to find his settlement disintegrating. He resumed his business — and his partying ways. The Puritans had had enough. They arrested him again, burned all his belongings, his house and most of Merrymount, and sent him back to England to face charges of selling guns and gunpowder to the Native Americans and “engaging in licentious behavior” with their women. He served a short jail sentence and went on to be an influential lawyer and author in England, writing the “New English Canaan” in 1637. In it he celebrated the beauty and bounty of New England but also sharply criticized the Puritans for their treatment of the Native Americans, too many of whom they killed or sold into slavery, and for imposing their strict and unbending religious doctrine into everyday law. The book made him a celebrity in England.

After 13 years in England, Cousin Thomas returned once again to Massachusetts, only to be imprisoned and, finally, exiled to the new colony of Maine.

Cousin Thomas would die there in 1647 at the age of 68.

Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote of Cousin Thomas’ struggles with the Puritans, “Jollity and gloom were contending for an empire.” I guess gloom won. But not without a dogged fight by my ancestor Thomas Morton.

The New England Historical Society summed up Cousin Thomas’ place in history this way: “Today, people might call him America’s first hippie.”

Cool. Now, how about a turkey leg and beer?