Underfunded and understaffed, Marion County’s mental health care system is making strides at improvement.

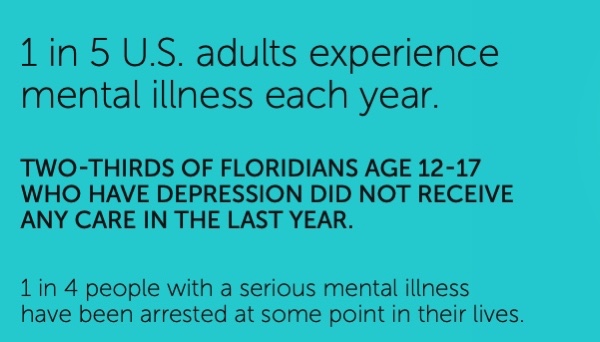

It’s an illness most of us don’t like to talk about. Not to our friends, not to our co-workers, not even to our family. Heck, not even to ourselves. Yet, experts say one in five of us are afflicted by mental illness each year and, even if we do recognize we need help, too many of us don’t know what to do or where to go.

For years, Marion County’s – and Florida’s – mental health care system has been woefully underfunded and inadequate. So obvious are the system’s shortcomings locally that participants in a recent Marion County Healthcare/Social Services Provider and Community Partner Survey deemed mental and behavioral health care and counseling the hardest health care services to access locally. Survey participants said it is twice as hard to get mental health care in Marion County as the second-hardest health service to obtain, substance abuse treatment.

For years, Marion County’s – and Florida’s – mental health care system has been woefully underfunded and inadequate. So obvious are the system’s shortcomings locally that participants in a recent Marion County Healthcare/Social Services Provider and Community Partner Survey deemed mental and behavioral health care and counseling the hardest health care services to access locally. Survey participants said it is twice as hard to get mental health care in Marion County as the second-hardest health service to obtain, substance abuse treatment.

In that same survey, participants were asked “the 10 most important issues to be addressed to improve health” in the community. Once again, mental health care was the overwhelming No. 1 concern by both healthcare partners and members of the community at large.

Of course, a lack of funding is at the core of the problem.

“Florida has lived with the 48th or 49th ranking (among the 50 states) in per capita mental health funding for years and has been okay with it,” said Rhonda Harvey, chief operating officer for SMA Healthcare, which last year took over operation of what was formerly The Centers. As a result, Harvey added, “Everyone has been very frustrated with the state of mental health services.”

Members of the National Alliance on Mental Illness-North Florida Chapter say that funding has been the most significant roadblock to providing adequate mental health care in Marion County for years. Specifically, they say the state’s refusal to accept Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act has left large numbers of Marion Countians unable to get care.

John Podkomorski, executive director of the North Florida NAMI, believes if Florida had accepted Medicaid expansion, which would cover insurance costs for the poorest in the community, the estimated 40 percent of uninsured mental health patients would be reduced to 10 percent.

More to the point, Podkomorski said that 85 percent of the mentally ill don’t get adequate care because they simply cannot afford it. He said the situation is exacerbated because people who do not get adequate mental health care typically do not get proper overall health care.

Curt Bromund, executive director of the Marion County Hospital District, said the absence of Medicaid expansion dollars is only part of the low-funding equation. He said Marion County mental health care providers in the past have not been aggressive or, worse, inept at pursuing public grants and other funding for local services. As a result, Marion County was foregoing available dollars simply because providers “didn’t follow protocols.”

The Hospital District, which has allocated nearly $15 million over the past three budget cycles to enhance mental health and behavioral services in the community, got involved in the issue because the inadequacies in the local system were systemic.

“It was overwhelming what we had to do,” Bromund said.

Robin Lanier, SMA vice president of Marion County services, said a big contributor to insufficient mental health service in the community can be summed up in two words: knowledge and navigation.

Lanier said there is too little public awareness of the services that are available and even less understanding of how to navigate the mental health care system once you engage it.

“There’s not an awareness of what services are available; and it’s also navigating the system, which can be difficult,” said Lanier, a Marion County native.

The NAMI-North Florida estimates that 20 percent of all Marion Countians will have some sort of mental health crisis this year.

Multiply that number by three, Podkomorski said, because family members or friends inevitably are dramatically impacted by a mental health crisis by someone they know.

Carali McLean, who is chairman of the NAMI-North Florida board as well as director of quality and risk management for the Heart of Florida Health Center in Ocala, said part of the solution to expanding mental health care is to incorporate it into their regular health screenings. That is something Heart of Florida has started doing, she said.

“It’s right there in the doctor’s office, so they don’t have to go looking for help,” McLean said.

Harvey and Lanier both said The Centers, Marion County’s largest mental health care provider, in recent years had created an uninviting culture that made it hard not just for people to get care but to get through the door.

“The reputation was bad for The Centers,” Lanier said. “… The crisis is really at the front door, which was difficult to get through.”

Her boss, Harvey, said treating patients locally is further complicated because too many of them do not understand that mental illness is not like other illnesses, where you get over it after some medicine and rest.

“With our population, they want to be one and done,” Harvey said. “They want to be ‘fixed,’ but we want people to realize this is a lifetime illness and it needs care…. Stigma is the biggest detriment to mental health care.”

It is more than individuals that suffer when the mental health system fails the community, too. Other organizations and institutions also are negatively impacted.

“Because The Centers had failed the community for so long, the hospitals became the default mental health center,” Harvey said, adding that it was costly to the hospitals and resulted in patients needing mental health care not getting it.

Same goes for the county jail, where up to 40 percent of the inmates under Sheriff Billy Woods’ watch suffer some level of mental illness.

Same goes for the county jail, where up to 40 percent of the inmates under Sheriff Billy Woods’ watch suffer some level of mental illness.

Law enforcement has been further frustrated because, until recently, the community had a woeful lack of detox beds – four for a community of more than 370,000 – and virtually no outpatient services. It also did not have any “medication assisted treatment” program for substance abusers.

If police picked up someone who was overdosing, they sometimes would have to drive them to Daytona Beach or Tampa to get them treatment, Ocala Police Chief Mike Balken has said.

Thankfully, the problems with mental health services in Marion County have not gone unnoticed or unaddressed. In fact, there has been a concerted and coordinated effort to improve both the accessibility and the breadth of those services.

The changes, which largely have occurred over the past three years, are highlighted by the change from The Centers to SMA Healthcare as well as the addition of the Hospital District’s new Beacon Point campus on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue, just north of State Road 200.

Beacon Point has been described by those in the mental health and substance abuse communities as “a game changer.”

“It is a really big deal for the community,” SMA’s Lanier said. “It’s really accessible and they provide just about any service they need.”

Beacon Point, which has been funded with some $15 million from the Hospital District, houses numerous programs, notably Park Place, Lifestream and some SMA programs.

Park Place provides new detox beds, clinical withdrawal management, residential drug treatment and peer support.

Lifestream, meanwhile, offers outpatient counseling, 12-step training, Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous programs.

Finally, SMA has medication-assisted treatment for the drug addicted as well as onsite assessment and case management.

Also on site is a primary care clinic – with psychiatric services – run by the Heart of Florida Medical Center and a Substance Exposed Newborn program run by Well- Florida that assists drug-addicted mothers and their newborns.

These are all critical services that were severely lacking – detox beds went from four to 18 or did not exist at all – prior to SMA; outpatient services were not available in our community.

Now, as one of nine pilot counties across the state, SMA, the Marion County Health Department, AdventHealth and the Hospital District are working to create an “addiction stabilization center” that will follow a drug-addicted person from the hospital emergency room all the way through the assessment and treatment process.

“This prescribes how to handle a person in substance abuse crisis,” SMA’s Lanier said. In addition to Beacon Point, envisioned as a one-stop center for assessment and care programs for persons suffering from mental or substance abuse, SMA is also making big changes at its main campus on Southwest 60th Avenue. After it took over The Centers in July 2021, Lanier said there was a significant amount of basic maintenance and repairs needed, some of which are ongoing. SMA is planning to expand the 60th Avenue Campus as well, hoping to add to its 35 adult drug treatment beds as well as the 12 juvenile beds. Expanded telemedicine is also part of SMA’s plans, although a significant number of people already receive care via Zoom and other online platforms.

Lanier said the goal is to change the culture at SMA Healthcare by making sure that when someone comes in search of mental health care, that “there is no wrong door.”

“When you walk through any of our doors, you’re going to have a positive experience,” she said.

Meanwhile, NAMI-North Florida is providing classes for people with mental health and other issues to help them cope with and overcome their conditions, Podkomorski said. The classes have about 10-15 participants and last 2 1⁄2 hours each week for eight weeks.

In addition, NAMI also offers The Clubhouse, which McLean called “the foundation of the organization,” because it acts as a work center for people with acute mental health issues.

What virtually all those involved in the many individual mental health agencies and programs serving Marion County agree on is that greater coordination and planning has resulted in better funding and better mental health services. At the same time, they also agree there is still plenty of work to be done, because Marion County is growing rapidly.

When asked what challenges remain for the mental health community, NAMI’s Podkomorski and McLean rattled off a list of remaining challenges.

Of course, funding will remain a challenge, given the state’s track record of poor funding of mental health care. In addition to that, however, they say the absence of long-term patient care within the community is a critical shortcoming. Also, finding enough specially trained workers continues to hamper the expansion of programs, even if there is enough money to do so.

Lack of housing and transportation also hinders Marion Countians’ ability to deal with their mental health problems.

Lanier, of SMA, reiterated that a big impediment to obtaining quality mental health care is simply a lack of awareness about what is out there.

She went on to say the coordination between SMA, the hospitals, Heart of Florida, the Health Department and Beacon Point programs has been beneficial to both the agencies involved and the community in general.

While there have been facility and program upgrades in the past few years, Lanier said that the biggest change in mental health care in Marion County has been the changes in leadership at SMA as well as other mental health partners, like the Hospital District and now Beacon Point.

The Hospital District’s Bromund said it goes even beyond the partnerships, although they have been critical.

“It’s not just the programs,”he said,“it’s the continuum of care that we have established.”

In other words, a person with a mental health or substance abuse crisis should be able to seek help at a number of different outlets and, because they are now working together, end up with a coordinated, long-term plan for care, whether you are insured or not.

“Poor mental health is related to everything – substance abuse, you lost your job, you have a personal crisis,” said Debra Vasquez, chief operating officer of the Hospital District. “With what is happening now in our community, it is extremely promising. With the integrated health care we are now seeing, they’re all working to provide individual service to the individual.”