Ocala nurse Donna Davis shares her experience at the pandemic epicenter in New York City

Ocala nurse Donna Davis shares her experience at the pandemic epicenter in New York City

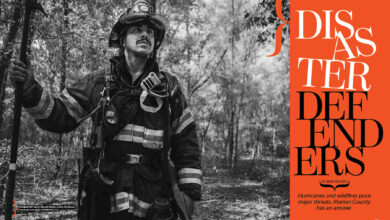

Among soldiers in the American Civil War, to have engaged in battle directly against the enemy was to have “seen the elephant” and many volunteered for service hoping to gain some invigorating, life-altering experience. In the current war with COVID-19, Elmhurst Hospital in New York City is the Battle of Antietam.

Consider Ocala’s Donna Davis then to have “seen the elephant.” As a traveling nurse who heeded the call at the onset of the pandemic, she earned the dubious assignment of the country’s viral epicenter in Queens, N.Y., where she would discover mounting casualties, confusion and chaos unlike anything she had ever witnessed during her years in the medical profession.

Arriving with other nurses to Elmhurst Hospital, the Davis group entered the fray just as the 101st Airborne drops into a hot zone – no moment to catch one’s breath or assess the situation, just the urgency to get in and fight. For Davis and many other nurses, the fight started and did not diminish for months.

“At the time, I didn’t know what I was walking into,” Davis said. “We had no clue if it was for real.”

That was in late March of 2020, when the nation was locking down and in a panic over a virus that just two months earlier leaders in the United States Congress, the White House and even the Centers for Disease Control stated “. . . this is not something that citizens of the United States right now should be worried about.” Forgive Davis for thinking at the time she was going to take on normal nursing duties then enjoy the city of New York for a little while.

What ensued was 21 straight days of 12-hour shifts dealing with a virus that did not behave like the normal flu. Hospital protocols for this novel coronavirus were wanting and were yet to evolve where efficiency and expertise had taken root.

Davis arrived after the battle had already commenced – bodies lying in hallways of triage, veteran nurses battered to exhaustive breaking points and new patients streaming in on a seemingly endless train of viral affliction. It became abundantly clear to Davis that this was the epicenter of something much larger than what she had planned.

“It was apocalyptic – a real mess,” Davis said. “There were patients in the hallways and they were stacked close to each other. It was dirty; there was stuff everywhere and they were very short-staffed.”

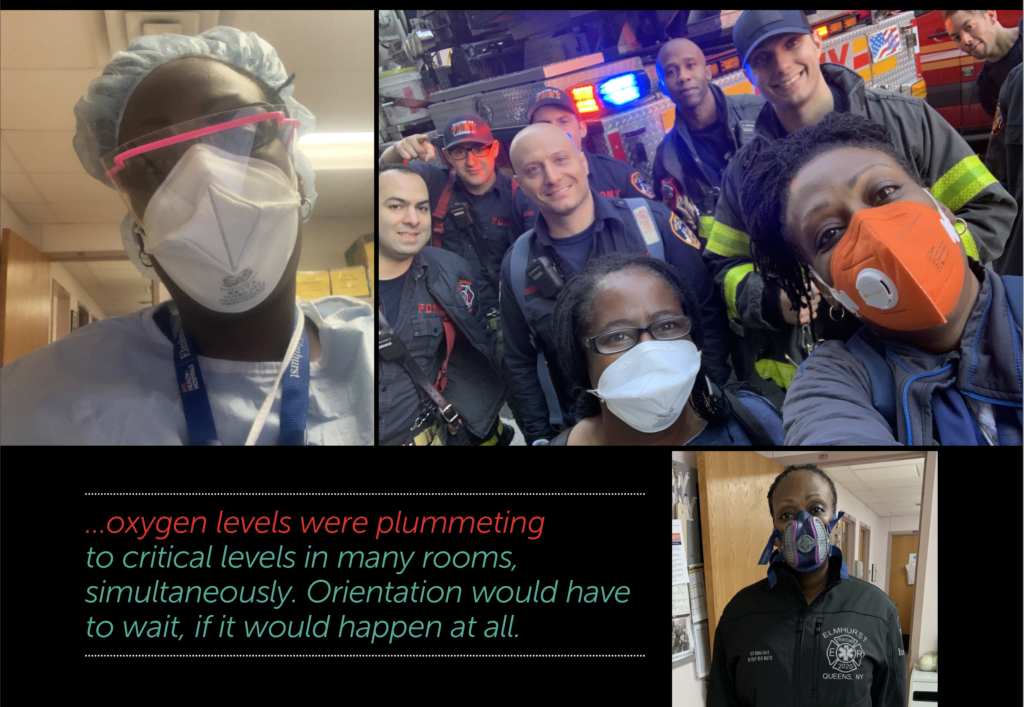

Upon arrival at the hospital, Davis and the other “nurses to the rescue” prepared for a simple orientation that would include proper donning of personal protective equipment, New York nursing protocols, the lay of hospital landscape and such. What started as a self-guided tour with a “treasure map” given to each nurse to help them locate relevant places with which to become familiar quickly turned into an all-hands-on-deck situation.

Over the loudspeakers blared “402 D-Sating! 402 D-Sating! 307 D-Sating!” Davis and the other nurses understood perfectly what was happening: oxygen levels were plummeting to critical levels in many rooms, simultaneously. Orientation would have to wait, if it would happen at all.

“We’re trying to find the stuff on our list and I notice all the nurses are in full-on PPE at the nursing station – this is not normal,” said Davis, fully aware that donning of gowns is supposed to take place going in and out of rooms. “No sir, everybody had COVID and everybody was really sick.”

The realization finally hit that half the nursing staff was out sick – no nurse would be able to take any time to orient the new arrivals to Elmhurst Hospital. Davis and the others were to “see the elephant” sooner than expected.

“We were like, ‘What do we do?’” Davis said about trying to rally the new nurses. “We huddled together and asked ourselves, ‘What can we do? What is our skill set that we can help?’

“I said, ‘Listen, we can all tech; we can draw blood. Let’s just jump in and start doing stuff. We didn’t do direct patient care, we just jumped in and started acting like extra arms.”

Davis says she remembers the nurses on duty hardly noticed them at the time – that was how busy they were.

“God bless these New York nurses!” she lauded. “They kept going and going and going, practically climbing over each other to check on these patients.”

Davis said the first night was the worst, but there was no letting up. As one patient left a room, another would fill that space within seconds.

Back at the hotel between shifts were constant reminders of the grim situation as news reports saturated the airwaves with headlines of the recent casualties that had taken place at Elmhurst and elsewhere. She was living the daily life of a M.A.S.H. unit with the perpetual sound of choppers hauling in wave after wave of wounded soldiers. But these weren’t infantrymen charging hills or beachheads, they were mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, grandmothers and grandfathers, all struggling for breath against a virus no one was certain how to combat.

“Death became just like another thing,” said Davis, who is also a practicing minister. “Because of all the people who died, you just numb out to it – it becomes part of the routine; ‘Oh, we lost that one.’”

With each death, Davis would appeal to a higher power. Often, she would sneak into the room of a recently deceased patient to pray for that soul.

“I don’t know if this person had a religion; it didn’t matter. I just thanked God for that person’s energy, whatever they did in the world, whatever people they touched.”

After Davis’ 21st straight day on the job, a small respite came in the form of a day off and a chance to see some of the city she had pined to visit. Walking around an empty Times Square was a surreal experience, certainly not like the images of teeming crowds and noisy traffic she remembered from pictures and television. Perhaps the juxtaposition of a quiet Manhattan offered the perfect escape from the bustling madness at Elmhurst.

Back to Elmhurst the following day and back to the grind, back to the arrhythmic tide of death and disease. By this time, Davis had moved from floor nurse to team leader with 123 nurses under her guidance for the night shift and methods were improving.

Paramount to the mission at this point was to relieve the lungs of fluid on a constant basis. This meant every 20 minutes a nurse was to “suction out the gunk” of those patients relegated to the use of ventilators.

“That’s how you saved lives,” Davis said. “You suction out the mucous and that’s why you need the ICU nurses – they became a big thing.”

Early on in Davis’ tenure, patients would arrive deep into COVID’s grip and often too late to save or beyond the safe use of therapeutics. Nearly all patients would endure either a noninvasive ventilation such as BiPAP or high-flow oxygen by nasal cannula before heading to ventilators. These became major sources of observation for the nurses, who were constantly wary of patients removing these devices.

With the nurse-to-patient ratio so low, the required constant supervision often suffered. Patients many times would remove oxygen devices to go to the bathroom which would lead to them passing out and sometimes dying. Others would sometimes panic once an oxygen device was administered.

“The only time we intubate a patient is when that patient can’t struggle (to breathe) anymore,” Davis said. “When you have a patient holding your hand saying, ‘I can’t breathe; help me,’ you try to put the BiPAP on them and because they’re so confused this feels very suffocating, so now they fight you to take it off.

“Now you have to sedate that patient and that’s when we have to put a ventilator on.”

Once the ventilator goes on, the chances of survival diminish. Davis remembers as time passed more patients would be weaned off ventilators and the extubation process would be cause for celebration. On one bus ride back to the hotel, the nurses were asked who had witnessed a successful extubation that day and many hands went up. Cheers ensued as though a glimmer of light had been detected at the end of a long tunnel.

“I had one patient, the tube came out and I noticed him on his phone texting! He was texting! How great was that?”

So why Elmhurst as the epicenter? Surely there were many other places around the country which experienced similar circumstances, but early in 2020 New York City suffered by far the largest number of cases and deaths, and in the city with the highest volume Elmhurst was the hardest-hit hospital.

Demographics certainly played a key as New York is and always has been the main port of international travelers to and from the United States and for immigrant populations in general. In the Elmhurst community is a population of which 70 percent were not born in the United States and many of the families are large and crowded into tight spaces.

It also did not help that in early March the New York mayor sent out tweets encouraging New Yorkers “To get out on the town despite Coronavirus.”

Amazingly, while Elmhurst was overrun, many hospitals in the city, including some just 20 minutes away in more affluent districts, were enjoying plenty of unused space. According to a May 2020 New York Times story, “3,500 beds were free in New York City” but little cooperation was taking place at that time between hospitals.

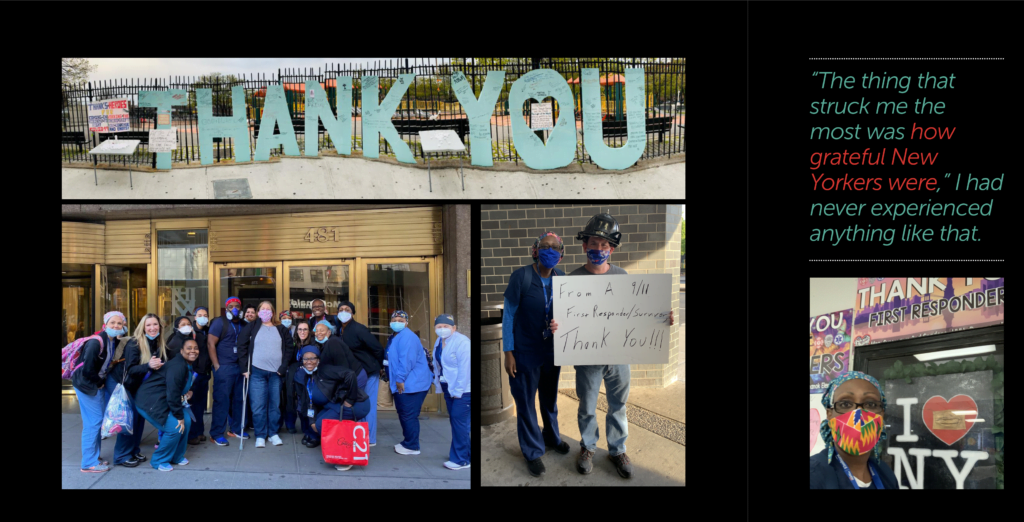

For Davis and the other nurses battling in the trenches of Elmhurst, nearby vacancies were of little thought or consolation. What did matter was her feeling the work did not go unappreciated.

“The thing that struck me the most was how grateful New Yorkers were,” said Davis, whose tour of duty at Elmhurst lasted three months. “Everywhere we went, they saw the scrubs and would say, ‘Thank you so much for coming!’ Almost every single shift we would come in, there were people honking and applauding us. I had never experienced anything like that.

“It boosts your self-confidence and makes you feel like what you’re doing is important. It strikes you that somebody cares.”

Davis recently returned to New York, working at Coney Island Hospital. She said the difference between then and now is “night and day.”

One main difference is that patients started checking themselves into hospitals during earlier stages of the virus, not waiting until it was nearly too late for treatment. Also, hospitals now have “protocols in place for supporting staff” better than before.

The result has been a dramatic easing of the hospital overcrowding, especially at Elmhurst. For a country which set out to “flatten the curve” of hospitalizations, it appears the efforts of Davis and many other traveling nurses has paid dividends.

A desperate nation called upon these heroes, and now a weary nation extends its gratitude for manning the front lines in this battle that now seems like a winnable proposition.