Al Dominguez withstood nine hours in the waters of Guantanamo Bay enroute to escaping Castro's Cuba

As young Al Dominguez swam Guantanamo Bay in the dark of night, his mind began to play tricks on him. Every ripple of a wave appeared as a shark fin and every nudge on his leg was surely to be followed by the clamping down of a predator’s jaws. His fears nearly overcame him, and likely would have, were it not for his insatiable thirst for freedom.

The year was 1965 and Dominguez, who is now enjoying retirement in Ocala after a successful career as a landscape architect, had decided life under Cuban dictator Fidel Castro was no life at all. At age 15, Dominguez made the extraordinary decision to swim the bay and reach the American military base where he could escape the communist regime that had taken power in Cuba just five years earlier.

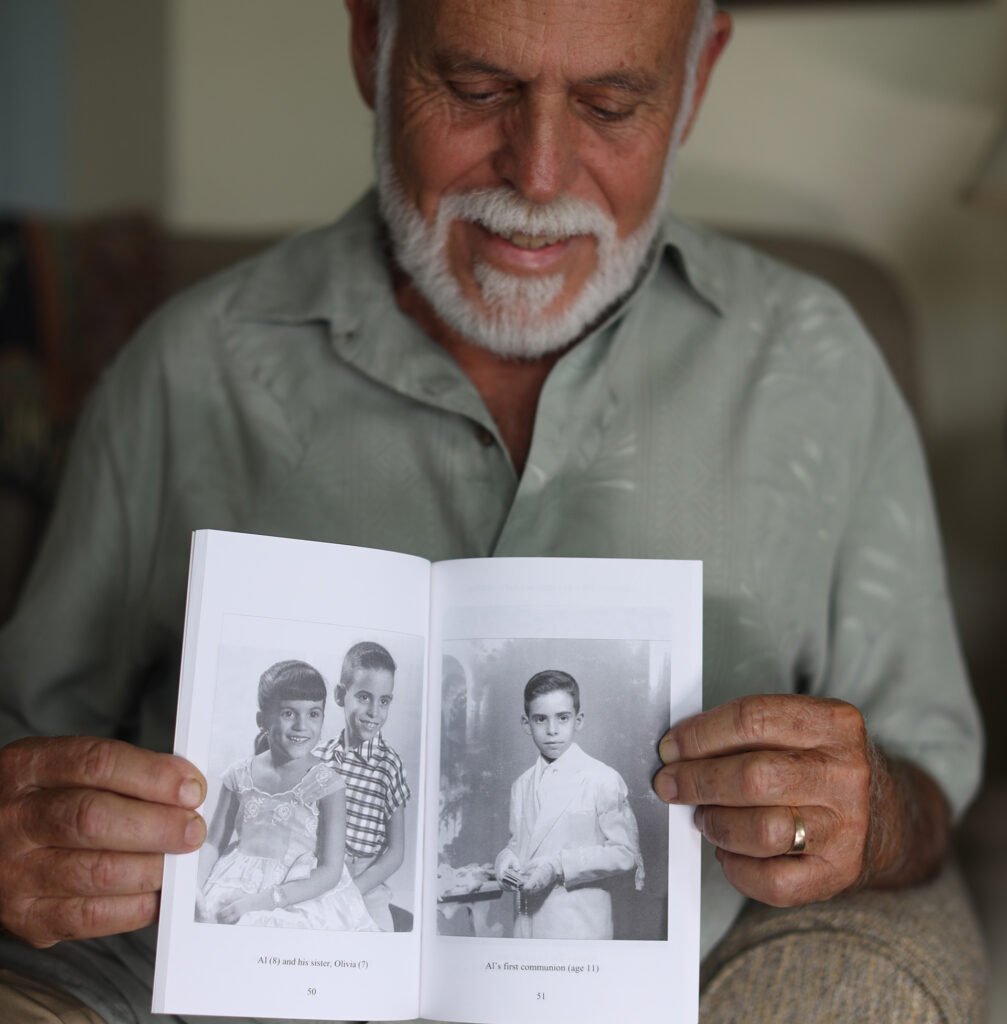

The story of Dominguez’ journey is told in Terry L. Clark’s book, “Swim to the Light: One Man’s Journey to Freedom,” and recounts idyllic days in Cuba before Castro’s takeover, the horrors of the Cuban Revolution, his family’s unsuccessful attempts at earlier escape and, most dramatically, the swim across the dark bay.

He would spend nine hours in the water, at times bumping into jelly fish and constantly under the real threat of shark attack. Cuban patrol boats and eventually the strafe of bullets around him meant threats to his life existed below and above the water.

“I think the most harrowing part was when the (patrol) boat came over,” Dominguez says of his watery escape in which search lights from the boats were nearing him and his companion Rafael, making the swim together. “We had to dive in that darkness and be under water trying to hold your breath and you hear the engine go over. You hold your breath until you feel you can’t anymore, then you come up for air.”

Coming up for air meant the risk of being spotted by the patrol boats, which certainly would have meant getting shot and left for dead in the water.

When he did come up for air, the boat had passed and Rafael was nowhere in sight. He would be alone for the rest of the swim.

Before his daring escape, Dominguez had experienced a wonderful childhood in which he traveled the entire island with his family. He visited his grandparents’ farm where they would swim in the lakes, go camping and do most of the things children do for fun in the outdoors.

“It was a beautiful paradise to me,” said Dominguez, who claims all his memories of Cuba are as vivid today as they were then. “We understood that (Fulgencio) Batista was a dictator, but we had a wonderful life until the last year and a half before Castro took over when things really got ugly.”

The final year and a half of the Batista regime meant war on the home front and tight control of the citizenry. Gunfire would often ravage the city and one day Dominguez and his sister were caught in the middle of it all while walking home from school. Amid the gunfire, he and his sister were able to crawl to a nearby house that offered protection.

At that moment, Dominguez’ mother decided it was time to leave the city of Guantanamo and head for their grandparents’ farm where there was no fighting. This meant sneaking out of the city in the middle of the night and making the trek by foot, which would take over a week.

“The farm was absolutely heaven. To me, that was absolutely beautiful, and that was taken away.

“It was not immediately taken away – the first year of Castro, he never declared himself communist. It was after the (1961) invasion of the Bay of Pigs that he tightened up and made life impossible.”

At one point after Castro had garnered power, the family moved to the city of Moron, in Camaguey, located in the north central part of Cuba. There, his mother was informed of a nearby port where Cubans could flee by boat to the Bahamas. This became Dominguez’ first attempt at escaping the island and turned into another disappointment.

Word of his family’s attempt to flee by boat had been heard by the authorities. Instead of a boat coming to pick them up, the family was greeted by Castro’s military personnel. The family hid in a small shack which the soldiers surrounded and demanded their exit. With arms over their heads, the family walked out of the shack like prisoners of war.

For several days, each member of the family was interrogated by soldiers at a nearby house. Al and his sister were eventually released, but the mother was sent to jail where she stayed for two months until the authorities figured she was of no threat.

“We knew of people that had been killed. The Cubans wouldn’t pick you up – they would shoot you and the sharks would take care of the rest.”

Before his swim to freedom, Dominguez trained and practiced in the water for weeks. During his training he befriended Rafael, who was five years older and planned on swimming to the U.S. base on Guantanamo Island – they decided they would make the trip together.

During the swim, Dominguez had been told to swim in the direction of the channel then head toward the light on the other side of the bay. After escaping the patrol boat and navigating the jelly fish, the shoreline was near but with more danger awaiting.

Dominguez would hear the cracking of guns from Cuban patrol towers on the shore. Soon, he would hear the bullets splashing into the water around him.

“We knew of people that had been killed. The Cubans wouldn’t pick you up – they would shoot you and the sharks would take care of the rest.”

Thankfully, the Americans could also hear the gunshots.

“Once they started shooting, the American side knew they were trying to kill the people that were trying to escape,” Dominguez recalls. “That’s when the American side would turn on this huge floodlight and blind the Cubans so they could not aim directly at the people – they were randomly shooting.”

He increased the intensity of swimming and eventually made it beyond the range of the bullets. Exhausted and cold, there seemed to not be enough strength in him to carry on. Then, he heard those beautiful words: “Tama el salbavida!” (Take the life saver). It was an American standing on a pier, throwing a flotation device to him.

Dominguez made it safely to shore and once there saw dozens of others who had made the same swim. Among them, to Al’s great relief, was Rafael. He’s not sure how many were killed that night making the attempt and U.S. army personnel exclaimed there were more in the water that needed to be saved.

To go through such a traumatic experience, Dominguez says was worth every second.

“I had no choice; I definitely did not want to live in that completely depressing environment,” he said. “I knew what freedom was, as my mom had been in the U.S. and came back, and she explained what it’s like.”

Once safely on shore, American servicemen attended to Dominguez, who was suffering from hypothermia – he had been in the water nearly nine hours during the month of October. He would be treated in a clinic then flown to Miami where he telephoned his aunt who was living in Orlando. She hurried to Miami and picked up the young Dominguez and brought him back to central Florida with her.

All the while, Dominguez’ mother had finally secured papers to leave Cuba and return to the United States through Mexico. She had no idea where her son was and knew she would eventually make the trip without him. At this point, the aunt arranged a phone call to inform Dominguez’ mother that he was safe in the U.S.

“My aunt told me not to say, ‘Hi, mommy!’ or anything,” Dominguez remembers of the phone call. “That’s when my aunt said, ‘I have a dear friend here with me that wants to say ‘Hi.’’ I said, ‘Hi, Olga!’ and my mom immediately recognized my voice. We heard her drop the phone and she fell on the floor screaming because she couldn’t believe it.

“She was leaving Cuba with a broken heart, thinking I was staying behind and that she might never see me.”

He would soon see his mother, but by this time Dominguez’ father was completely out of the picture, having divorced his mother when he was age 7. His father was a supporter of Castro and even before the collapse of the Batista regime had been very distant with his family. Estranged from his father, once Dominguez reached the United States, he knew he would never be able to make peace with him.

“During the wonderful times I had with my family, my father was never there,” Dominguez said. “Once we left, he said we might as well be dead.

“The thing that hurts so much is that the communists believe in the breakdown of the family and our family became divided.”

Dominguez said he was never able to make peace with his father, but that he has done so in his heart. “That was very painful – I did some therapy in trying to heal from that pain.”

Dominguez parlayed his love for the outdoors and strong work ethic into a degree from the University of Florida and that led to his career in ornamental horticulture. He remembers the drive from Gainesville to Orlando and how the country in between especially intrigued him.

“I always took the off-roads traveling the central part of Florida and I fell in love with this area. It’s more rolling, more country; the horse farms and the lakes are beautiful. I said, ‘This is it! I don’t want to go back to Orlando or south Florida.”

Answering the rural siren call of Marion County, Dominguez went to work for Richard Kesselring at Green Tree Nursery in Ocala. That marked the first step in a great career in landscape architecture, from which he only recently retired.

“Every single day, I praise the Lord,” Dominguez says. “My life is incredible – what I’ve experienced, I’ve been so blessed.”

In July, Cuban people took to the streets in defiance of the government. Demonstrators chanting “Down with the dictatorship!” spurred some hope among people in the U.S., especially those of Cuban descent. But Dominguez does not share that optimism – he knows where the Cuban government’s priority rests, in maintaining its stranglehold on the people.

“They squashed it so hard,” Dominguez assesses the current situation in Cuba, where hundreds have been detained, police are staking out homes of activists and fear is gripping the population as the crackdown seems far from over. “I have friends that go (to Cuba) because they still have children and grandchildren there, and they come back with nightmare stories. With COVID, they are in complete lockdown. The entire week you are allowed one day out to go shopping. If they catch you outside, they beat you up and fine you a huge amount of money, and if you can’t pay, they throw you in jail.

“(The government) Has total control of the island – you cannot move anywhere. There are no firearms or anything that the people have that can help them.”

These days, Dominguez often finds himself perusing Google Earth, looking at the current images of all the places he used to visit as a boy. The memories return in vivid fashion and the emotions quickly swell as he hearkens back to grand times as a child. The images he sees break his heart.

“It’s so painful. I see how destroyed, how ugly everything is.”

Dominguez has promised himself that he will only continue to look forward and not dwell on the past. He is an American and has no desire to ever return to Cuba, at least as long as the communists maintain control there. “I don’t want to go back, never.”

Dominguez says he tasted enough of what life is like under communism during his time under Castro and even during visits to Eastern Europe before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“When I was in Europe, especially Romania and Bulgaria, it brought back memories of Cuba, how horrible and destroyed it was,” Dominguez said. “I cried. I told my wife: ‘This just breaks my heart; I feel like I’m walking in Cuba.’

“I know when I arrived in this country, here in Florida, I swore right there I would never look back. Unless that nation becomes free again, I don’t ever want to step in there.”

For the man who swam Guantanamo Bay to freedom, life has turned out pretty well. “I’m so blessed. The thing that always helped me through these tough times was my belief in Christ. He never left me and saved me from the bondage of communism.”